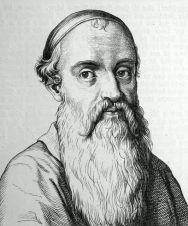

Biographical Sketch

by Garrett McQueen, Biola University

Summary of life:

1489- Born in Stolberg

Education:

- Studied at the University of Leipzig in 1506

- Studied at the University of Frankfurt in 1512

Work:

- He was an assistant teacher in Halle in 1513 and a clergyman and teacher in Aschersleben from 1514-1515

- He worked as a prior at Frohse monastery at Aschersleben from 1516-1517

- He taught at the Braunschweig Martineum until 1518

- He pursued literary studies at Beuditz monastery at Weissenfels from 1519-1520.

- In 1520 he became a preacher at the Marienkirche at Zwickau, and here he became more publicly known

Influence and recognition:

Influenced By:

- Martin Luther– influenced Thomas Müntzer as through the posting of the 95 Theses, for Müntzer met Luther in Wittenberg in 1517 and was involved in preliminary discussions about the posting. Luther’s reform ideas influenced Muntzer towards reform. Through Muntzer’s presence at the disputation in Leipzig, Luther recommended him to a preach in Zwickau.

- Nikolaus Storch– a leader of a reform group called the “Zwickau prophets” who led Müntzer to believe that “true authority lay in the inner light given by God to his own, rather than in the Bible”.

- Influenced by Mystics such as: Meister Eck and Johannes Tauler, but particularly Joachim Floras

Influenced:

- Thomas Müntzer influenced the peasants and common folk throughout his life, preaching that in view of their poor condition, they were God’s elect, meant to bring about his will to the world, specifically the millennium.

- The sect he joined in Zwickau influenced prominent people such Christian theologian Andreas Karlstadt, Christian reformer Philip Melanchthon and Martin Luther

Known for:

- Speaking out against the Franciscan order, the Roman Catholic ecclesiastical hierarchy and the veneration of saints.

- Claimed to be the founder of the Anabaptist movement:

- Anabaptists believed “they were the true elect of God who did not require any external authority” (Jasper Ridley, Bloody Mary’s Martyrs)

- Believed in separation of church and state, the state had no right to punish or execute anyone for religious beliefs or teachings-radical notion-every government in Europe saw them as a potential threat of both religious and political power

- they denied infant baptism, and denied divinity of Christ, they advocated a form of communism, denouncing private property

- Joining a Mystic sect of cloth-workers at Zwickau in 1520:

- This sect experienced many visions and ecstasies. The Patrician counsel in Zwickau forbid them to preach, and after Müntzer encouraged them to disobey that restriction, new prohibitions of prosecutions and imprisonments followed. 1521, the group of cloth-workers fled the town.

- Müntzer fled to Prague and began preaching against the clergy and preached against “the dead letter”, he believed it was necessary to receive supplemental inspiration of elect persons. At Prague he published a manifesto in which he initiated a final Reformation which included a new church led by the Holy Spirit. However, his preached was unsuccessful because the city had been exhausted with to religious fanaticism for too long.

- Set up a type of communist society in Muhlhausen in March of 1525 from which came the Peasant’s war

- Being at great odds with Luther as his theological convictions changed and grew

- He did not always agree with Luther and proved to be an independent thinker. Later found Luther a lukewarm reformer, particularly because of his bibliolatry, and Luther’s his accepting of certain church dogmas while rejecting others. (Ernest Belfort Bax, Peasants’ War in Germany)

- “The monks had such big mouths that if one would cut off a few pounds[from their mouths] there would still be enough left with which they could continue their nonsensical prattling.”

- Müntzer’s teachings disagreed with Luther’s doctrine of justification and the sola scriptura.

- He preached in Glauchau, gathering many followers, and in 1522 he arrived in Halle where he may have met his future wife, Ottilie von Gersen, who he married and had two children with.

- In 1523 he became a preacher in Allstedt. Muntzer’s provocative preaching style in Allstedt caused Luther to write a letter to George Spalatin(a Lutheran living in the area) advising all Lutherans to withdraw support of Müntzer for Luther said he “abused scripture” and that his preaching style had led to violence.

- Thomas Müntzer formed the Allstedt League, a society committed to reform.

- At this time Robert Friedmann claimed, “Muntzer lost altogether his sense of reality and embarked on a road of romantic fanaticism”. (Robert Friedman, Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online)

- Müntzer claimed that his teachings came from the Holy Spirit.

- In 1524 Thomas Müntzer arrived in Muhlhausen. He believed his ideas should be applied to economics and politics as well as religion.

- Frederick Engels wrote that Müntzer believed in “a society with no class differences, no private property and no state authority independent of, and foreign to, members of society”(Frederick Engels, The German Peasants’ War)

- He believed peasants were God’s elect and would further his will to the world.

- In March 1525, Müntzer succeeded in taking over the Muhlhausen town council and setting up a type of communist society. By the spring of the 1525, Muntzer’s actions had caused a rebellion known as the Peasants’ war, and this rebellion had spread to much of central Germany. This war arose from a desire for old privileges of the system of serfdom and a removal of injustices. Eric W. Gritsch explains this system of serfdom, “From the ninth until the twelfth century, feudalism had been a relatively well-ordered social structure in Europe. It was based on the Teutonic kings’ practice of offering land, knows as “fiefs” to the most loyal members of their army.” Gritsch explains that these fief holders were awarded land, and peasants tilled the land. The serf owned part of the land that he tilled for the landlord and he would divide resources with the rest of the community. However, when Roman law had greater influence in Europe, the peasants were oppresses because their status became determined on the amount of owned property. This meant increased labor for peasants. (Reformer without a church). The peasants published their grievances in a manifesto title The Twelve Articles of the Peasants. The document asked that their demands should judged by the Word of God.

- Luther had no sympathy for the peasant and said “The pretenses which they made in their twelve articles, under the name of the Gospel, were nothing but lies. It is the devil’s work that they are at…. They have abundantly merited death in body and soul. In the first place they have sworn to be true and faithful, submissive and obedient, to their rulers, as Christ commands… Because they are breaking this obedience, and are setting themselves against the higher powers, willfully and with violence, they have forfeited body and soul, as faithless, perjured, lying, disobedient knaves and scoundrels are wont to do.” (Luther also published a tract titled Against the Murdering Thieving Hordes of Peasants.)

- Despite this, Thomas Müntzer led about 8000 peasants into battle in Frankenhausen on May 15th 1525. Muntzer’s rally was “Forward, forward, while the iron is hot. Let your swords be ever warm with blood!”

- They should no chance against the armed soldiers of Philip I of Hesse and Duke George of Saxony. Over 3000 peasants were killed. (Hans J. Hillerbrand, Encyclopedia Britannica)

- Müntzer was captured 10 days later. And as he awaited his execution, he wrote a letter to his friends in Muhlhausen from his prison in Heldrungen in which he asked them to care for his wife and dispose of his possessions. (Eric Gritsch, Thomas Müntzer: A Tragedy of Errors)

Death:

- Müntzer was tortured and executed on May 27th, 1525. His head and body were displayed as a warning to all those who preach treasonous doctrines. (Hillerbrand, Encyclopedia Britannica)

Original Works:

- “His most important religious, liturgical and theological writings originated there. They included German Church Office, German-Protestant Mass, Protestation or Defense…Regarding the Beginning of the True Christian Faith and Baptism, Of Written Faith and Precise Exposure of False Belief.” (Paul Wappler)

- Compiled works: Revelation and Revolution: Basic Writings of Thomas Muntzer

Secondary Works:

Eric W. Gritsch, Thomas Müntzer: A Tragedy of Errors

Tom Scott, Thomas Müntzer: Theology and Revolution in the German Reformation.

Bibliography:

(john@spartacus-educational.com), John Simkin. “Spartacus Educational.” Spartacus Educational. Accessed October 11, 2016. http://spartacus-educational.com/Thomas_Muntzer.htm.

Bax, Ernest Belfort. The Peasants’ War in Germany, 1525-1526. New York: A.M. Kelley, 1968.

Wappler, Paul. Thomas Müntzer in Zwickau Und Die “Zwickauer Propheten.”Gütersloh: Mohn, 1966.

“Thomas Muntzer.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Accessed October 11, 2016. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Thomas-Muntzer.

Engels, Frederick. “The Peasant War in Germany.” By Frederick Engels 1850. Accessed October 11, 2016. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1850/peasant-war-germany/index.htm.

“Müntzer, Thomas (1488/9-1525).” – GAMEO. Accessed October 11, 2016. http://gameo.org/index.php?title=Müntzer,_Thomas_(1488/9-1525).

Ridley, Jasper Godwin. Bloody Mary’s Martyrs: The Story of England’s Terror. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2001.

Summary of life:

Summary of life: